Why large MoE models break latency budgets and what speculative decoding changes in production systems

Why large MoE models break latency budgets and what speculative decoding changes in production systems

Large mixture-of-experts (MoE) language models promise step-function gains in quality. In practice, teams that try to deploy them inside real products often hit the same wall: latency that looks acceptable in benchmarks but collapses under production constraints.

This is not a failure of hardware or modeling — it is a failure of mental models.

This article lays out a practical way to reason about why large MoE models break latency budgets in real products, and which architectural choices actually change the outcome. The focus is not on demos or averages, but on systems that must hold under worst-case inputs, tail latency targets and real user behavior.

Part 1. A mental model for why large MoE models break in products

Throughput is the wrong starting point

Most inference discussions start with throughput. Tokens per second. Requests per minute. Accelerator utilization.

For interactive products, this framing is misleading.

What users experience is end-to-end latency. What breaks products is not the mean, but the tail. P90 and P99 are the real acceptance criteria, whether or not they are written down explicitly.

Large MoE models are uniquely punishing here because they stretch multiple dimensions at once: long context windows, non-trivial decode lengths, expert routing overhead and sensitivity to queueing under even moderate concurrency. Throughput numbers hide all of this.

Prefill dominates before decode even matters

For long-context workloads, prefill is the dominant cost. At input sizes on the order of ten thousand tokens, a large fraction of total latency is spent before the model generates a single output token.

This cost is paid in full for every request — it cannot be amortized away by batching without directly impacting tail latency.

MoE architectures amplify this effect. Even though only a subset of parameters are active per token, expert routing introduces additional memory traffic and less predictable access patterns. Two systems with very different peak compute characteristics can therefore exhibit surprisingly similar end-to-end latency for the same workload.

At this point, raw compute is no longer the bottleneck.

Why scaling replicas does not fix P99

When latency misses targets, the instinctive response is horizontal scaling. More replicas reduce queue depth and improve averages.

This often helps the mean, but it rarely fixes the tail.

Under sustained load, long-context requests magnify small variations in execution time. Once the system crosses a certain concurrency threshold, P99 latency stops improving smoothly and begins to cliff. Adding capacity beyond that point yields diminishing or even negative returns for tail behavior.

This is why systems that appear healthy at low traffic suddenly violate SLAs at moderate load, despite reasonable utilization metrics.

Streaming masks problems that non-streaming exposes

Many modern chat interfaces stream tokens as they are generated. This masks prefill and early decode latency by surfacing partial output quickly.

Non-streaming products do not have this escape hatch.

If the user sees nothing until the full response is ready, end-to-end latency is the only metric that matters. Time to first token still matters for future modalities like voice, but it does not rescue the current interaction.

This distinction alone explains why many MoE deployments succeed in demos and fail in products.

Cascaded systems tighten budgets further

Real products rarely run a single model. Safety classifiers, guards, rerankers or post-processors often sit before or after the primary model.

Each stage consumes part of the latency budget.

A system that barely meets a ten-second target in isolation is usually unusable once placed inside a cascade. Headroom matters. Tail behavior compounds.

This is why evaluating large models in isolation is insufficient. The unit of analysis must be the system, not the endpoint.

The critical shift in thinking

The core shift is this: large MoE inference is not a throughput problem — itis an execution-path problem.

Once you adopt this framing, many familiar tuning strategies lose relevance. The question is no longer how to shave milliseconds off average decode speed, but how to reduce the amount of expensive work that sits on the critical path.

That leads directly to architectural changes, not parameter tweaks.

Part 2. Speculative decoding as architecture for long-context, non-streaming systems

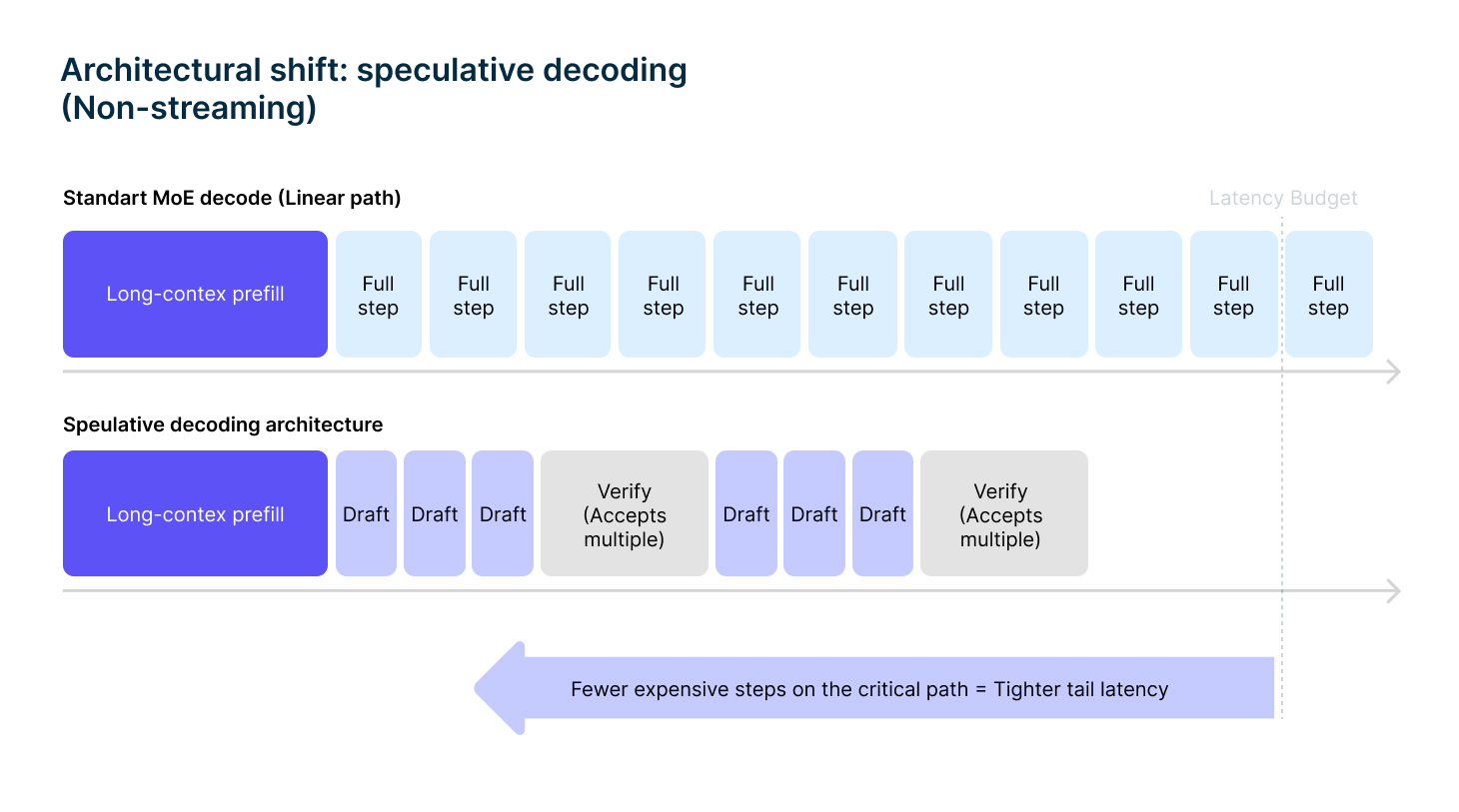

Why speculative decoding changes tail behavior

Speculative decoding is often presented as a throughput optimization. In long-context, non-streaming systems, its real value is different.

It reshapes the latency distribution.

In a baseline setup, every output token is generated by the full model. For large MoE models, each decode step incurs expert routing, memory access and synchronization costs. Under load, this leads to long, variable decode tails.

Speculative decoding alters this execution path.

A smaller draft model proposes multiple tokens ahead. The full model then verifies these tokens in chunks rather than generating each token independently. Verification is cheaper than generation, and multiple tokens can be accepted in a single step.

The result is fewer expensive operations on the critical path.

Why this matters more for non-streaming responses

In non-streaming products, users do not benefit from early tokens. All perceived latency is back-loaded.

Speculative decoding directly reduces the total number of full-model decode steps required to produce the final response. This has a disproportionate effect on P90 and P99 latency, which is exactly where long-context systems tend to fail.

Requests that previously straggled now complete within a tighter bound.

Quality does not have to be traded for speed

A common concern is that speculative decoding requires aggressive quantization or sacrifices output quality.

This is not inherently true.

Speculative decoding does not replace the full model. The full model remains the final authority. Draft tokens are verified and rejected if incorrect.

This allows the primary model to run in higher precision modes, preserving output quality. The quality risk is concentrated in the draft model, not the main model.

Draft model training as post-training infrastructure

The effectiveness of speculative decoding depends heavily on the draft model.

A generic draft model already delivers gains. A draft model, shaped through post-training on synthetic inputs that resemble real production conversations, delivers more consistent acceptance rates and tighter tail latency.

This is an important distinction. Post-training here is not about improving model quality in isolation — it is about adapting execution behavior to the product’s input distribution so that performance guarantees hold under stress.

Treating draft model training as part of the production pipeline, rather than an experiment, is what turns speculative decoding into a reliable architectural primitive.

Why speculative decoding must be designed in early

Retrofitting speculative decoding late in a project is painful. It touches serving pipelines, batching behavior, memory management and observability.

Treating it as a first-class primitive from the beginning allows teams to reason coherently about capacity, headroom and failure modes.

For long-context, non-streaming systems, speculative decoding is not an optimization — it is a prerequisite for meeting real product SLAs.

What this implies for production inference platforms

Across teams and use cases, the pattern is consistent: products fail when architectural decisions are postponed or hidden behind averages. They succeed when execution paths are designed explicitly around worst-case behavior.

This is the class of problem that Nebius Token Factory is designed to support: running large open-source models in production with explicit control over execution paths, governed post-training, predictable tail latency and isolation by default, rather than relying on opaque abstractions or optimistic benchmarks.

The goal is not faster demos. It is systems whose behavior under stress is understood, measured and bounded before users ever see them.